Ep. 5: Artist on the Edge: Mexican Muralism Shapes a Life

New York City’s dynamic and exploratory art scene of the early 1930s included exposure to the bold work being done by Los Tres Grandes—José Clemente Orozco, Diego Rivera, and David Siqueiros—the “Big Three” of Mexico’s muralism movement.

From left: David Siquieros, Jose Clemente Orozco, Diego Rivera.

The Big Three had become internationally recognized and produced some of their most important works in the United States. Each focused on a world view that supported the importance of the common man, the laborer, the working class—and rejected war, colonialism, and order imposed by an immune wealthy class.

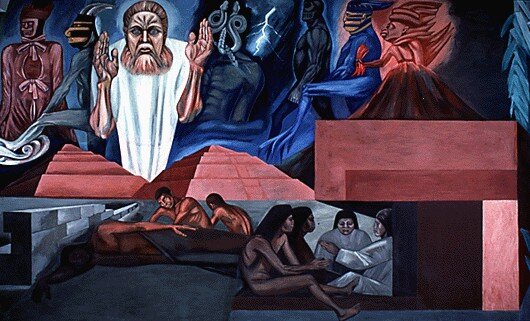

Orozco painted Epic of American Civilization, his mural for the reading room at Dartmouth in Hanover, New Hampshire (now in the Hood Museum of Art there), starting and stopping to produce studio work in New York where he had seven paintings and four drawings on view in a traveling Metropolitan Art Museum exhibit that toured eight other US institutions.

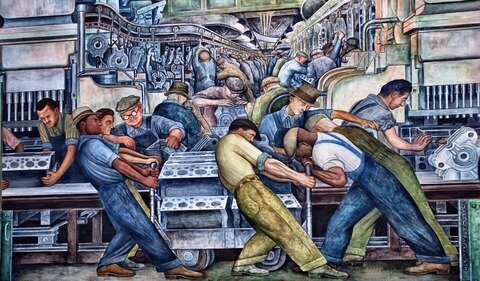

Rivera began his astounding murals for the Detroit Institute of Arts, his most important US commission, which still thrills visitors today (for a video tour of the project, click here. His major retrospective at New York’s Museum of Modern Art set new attendance records.

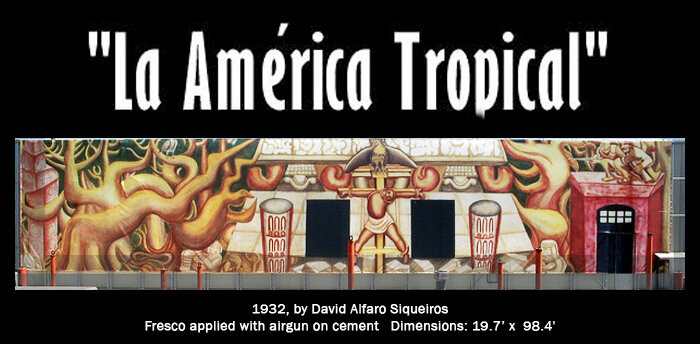

Siqueiros was in the West lecturing on modern means of painting outdoors, where he completed La América Tropical at the America Tropical Interpretive Center on Oliveira Street in Los Angeles, a mural that became the focus of a bitter debate with the city about the subject matter, causing it to be painted over. It was ultimately restored more than four decades later.

In 1934 Rivera began the mural Man at the Crossroads for the RCA building at the Rockefeller Center in New York City, only to be dismissed before completion. He had proposed a 63-foot-long portrait of workers facing symbolic crossroads of industry, science, socialism, and capitalism. A heated controversy arose concerning inclusion of Soviet leader Vladimir Lenin. Rockefeller ordered Rivera to remove the offending image. Despite negotiations to transfer the work to the Museum of Modern Art and demonstrations by Rivera supporters, near midnight on February 10, 1934, Rockefeller Center workmen, carrying axes, demolished the mural. The public outrage lasts to this day.

Later, Rivera recreated his composition in Mexico, calling it Man, Controller of the Universe, which is still on display at the Palacio de Bellas Artes in Mexico City. The story of the original mural's creation and destruction is the focus of a Mexican Cultural Institute exhibition in Washington, D.C.

Annette met Diego Rivera while she was at Columbia, when he was painting at Rockefeller Center. She also met José Clemente Orozco, at an exhibition of his work at Delphic Studios, Alma Reed’s gallery. Orozco liked Annette and invited her to come down to Mexico to do murals. Then she met David Siqueiros when he lectured about using commercial paints and spray guns in outdoor mural painting.

By now Annette had gathered quite a collection of the artists’ work. She went to the Weyhe Gallery on Lexington and bought many of Rivera and Orozco’s early lithographs and etchings, and a “blue period” etching by Picasso for $75 that she kept the rest of her life.

The Mexican muralism movement and these artists’ innovative and creative styles, the rumors and realities of their free-wheeling lifestyles, the missions their work proclaimed—all of these stimulated Annette’s longing for adventure, for a larger life. She may very well have felt it a challenge to all artistic pursuit and freedom when work such as Rivera’s powerful Man at the Crossroads was destroyed, perhaps recalling the painful censorship and disappearance of her own controversial portrait while at Hunter College.

By now, Annette and Sidney Pepper had a daughter—Cecily Deirdre Pepper (known throughout her life as “Cherry”). But the marriage was not going well and tensions mounted as Annette tried to balance her roles as wife and mother with her strong desire to pursue a career as an artist. In the summer of 1935, during a vacation trip to Mexico City with Sidney, Annette would meet ruggedly handsome, successful textile industrialist Louis Stephens. It was an event that would tip her over the edge and into a new life, following her passions, damning convention.